|

| Home | Milieu & Energie | Gezondheid & Wetenschap | Duurzaam Bouwen | Photo Gallery |

| Geologie & Reizen | Landbouw & Voeding | Natuurbescherming | Eilanden | Publications |

|

[home] Shell banks in the city © Annemieke van Roekel, 2011  Read Dutch version in Gea (pdf, 6,52 MB) >> Read Dutch version in Gea (pdf, 6,52 MB) >>Beautiful sections of fossil brachiopods from the Early Carboniferous in the center of Amsterdam were the reason to visit the quarry where these shell banks are: in Paulstown, Co. Kilkenny, Ireland. It is one of the four major limestone quarries in the South East of Ireland where - fossil rich – bluestone is extracted that has the quality for a building material. From this quarry each week one container "Kilkenny Blue Limestone" is shipped to the Netherlands, with final destination Amsterdam. “Our quarry is one of the 4 largest decorative bluestone producers in Ireland,” says Colin Feely, owner and director of the firm Kilkenny Limestone Ltd. This quality limestone is suitable as building blocks and is mainly applied as paving stone and wall covering. All 4 bluestone producers are located in the Southeastern part of Ireland, in County Kilkenny and the adjacent county Carlow. There are also a number of quarries in Ireland where a lower quality limestone is mined. This type of limestone - crush stone - is grounded and used in road construction, as backing for asphalt roads. Crush stone comes from chalk sediments with more cracks or where more layers with impurities (like iron) occur. "In this quarry, the limestone layers are between 40 cm and two meters thick," says Feely, “which is the minimum thickness for commercial mining."

Paleozoic sea life The Kellymount limestone quarry in Paulstown covers a total area of 75 acres (30 ha) of which 4 acres (about 1.5 hectares) is the open part. The quarry contains in fact 3 smaller quarries that will become one in the near future. The limestone has already been extracted up to a depth of 50 meters; the remaining recoverable limestone beds reach to a depth of 20 meters. 20% is sold as building material under the name "Kilkenny Blue”. 80% ends up as crush stone. The quarry has three shell banks, where the concentration of fossils is very high. Large blocks with a size of 2.5 x1, 5x1, 5 meters are extracted from the quarry with a steel chain saw with diamond. A water-cooled trimming saw removes rough edges from the big blocks and cuts them into smaller blocks. A water-cooled frame saw – also with diamond - cuts the blocks into 2 cm thick plates. The sediments date from the early Carboniferous, between 360 and 320 million years ago. During this period, Western Europe was located near the equator and covered by a shallow sea. Marine life consisted a.o. of sea lilies (crinoids), brachiopods (the most dominant shellfish in the Paleozoic that represent a unique phylum within the animal kingdom) and corals. These organisms became extinct at the end of the Permian era. Irish bluestone is comparable to bluestone form the Ardennes (Belgium), both in age and fossil content. Both areas belonged to the same shallow tropical sea during the Lower Carboniferous. Belgian bluestone is approximately 10 million years older and sea lilies are usually more dominant (visible) whereas Irish bluestone contains more and larger brachiopods (mainly productid brachiopods) and large corals. This applies to stone in various applications that we usually get to see as window sills, thresholds and counter tops in kitchens. The name "marble" or “granite”, often used for this type of bluestone, originates from the small fragments of stems of crinoids, but with real marble or granite this sedimentary rock has no connection.

Family business Feely continues a family tradition that goes back more than two centuries. The Irish family is active in the stone business already for ten generations. 230 years ago his great-grandfather started a masonry in Boyle, Co. Roscommon, in the North-West of Ireland, for the production of gravestones. This business, Feelystone, now also processing imported natural stone, is owned by Colin's brother Patrick. While the production of granite from Ireland, such as Co. Wicklow, has declined in recent decades, the popularity of Irish bluestone both in Ireland and abroad has increased. Besides limestone and granite, marble, sandstone and slate are quarried in Ireland on a small scale. The most recent ‘boom’ for Irish bluestone started in 1995. At this moment, the internal market has come to a halt due to the economic crisis and the crisis in the building sector. Feely: “Prices have reached a minimum in Ireland. However, we are still selling to our clients on the European continent. Apart from The Netherlands, Belgium and Germany is the main market. Kellymount quarry in Paulstown is not open to the public. However, these fossils are common in Ireland and can easily be found in the field. "The finest specimens can be found near the coast," says Michael Simms, curator of the fossil collection of the National Museums of Northern Ireland in Belfast. Interesting sites include Streedagh Point and Serpent Rock, both in Co. Sligo. "Both sites are well protected by the state. What makes Streedagh Point even more special is that there’s a succession of layers strewn with fossils corals, brachiopods and other ancient marine organisms. Each layer represents, in effect, a former seabed. Some corals can be seen three dimensional as the limestone surrounding the calcite fossil is etched away by rain and the sea." In the fantastic karst landscape of the Burren in Co. Clare, Mullagh Moor is a fine destination with corals and brachiopods from the Lower Carboniferous to admire, adds Simms. “And Bundoren (Co. Donegal) offers beautiful crinoids and brachiopods. In Northern Ireland, in Co. Armagh, some small quarries can be interesting to look for various kinds of brachiopods, and also fish teeth.”

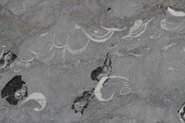

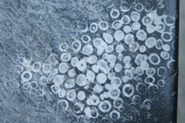

Corals and shells In the center of Amsterdam in the past decades, bluestone from Kilkenny is used for refurbishment of streets and sidewalks. The municipality of Amsterdam has decided to use curbs of Irish bluestone used as Belgian bluestone was traditionally used in cladding and stairs of the canal houses and other old buildings in the city. Therefore, the dark blue-gray color of Irish bluestone harmonizes very well to the existing architecture. Irish bluestone pavement and curbs can be easily recognized by large sections of the shells, sometimes up to 10 cm in the shape of a crescent or (double) circles. The sections of the ‘bushy’ corals measure up to half a meter. The brachiopods belong to the group of the productids, an important group during the early Carboniferous with a concave and convex valve; the bushy colonial corals are either Siphonodendron or the somewhat smaller Syringopora.

|